Communication with other apps

The Android system is designed to enhance security by placing each app within its own sandbox. This isolation prevents apps from directly interacting with one another or exchanging data without explicit permission. However, is it practical for an app to handle all functions independently? Typically, developers build apps to focus on their core business logic, leveraging the capabilities of other apps when necessary.

For instance, consider the inclusion of a contact number or email option for feedback within an app. One approach could be to integrate an email client and phone dialer directly into the app. However, developing such extensive features — akin to creating a full-fledged service like Gmail or a sophisticated dialer — could distract from the app’s primary purpose. A more efficient alternative is to redirect users to the existing email and phone dialer clients already installed on their device.

Similarly, when sharing a Google Maps location from an app, one option is to embed a web view displaying Google Maps within the app to provide directions. Alternatively, the app could redirect users to the Google Maps app — or any other navigation app available on the device — which is better equipped to manage such tasks effectively.

This is where intents come into play, facilitating seamless interaction between apps while maintaining focus on their specialized functions.

Intents

Intents are the core messaging units in the Android ecosystem, enabling communication between app components. They facilitate interactions both within a single app and across different apps.

To communicate within your app — such as between activities, services, or broadcast receivers — use explicit intents. With explicit intents, you specify the exact component to target by providing its fully qualified class name. This direct approach ensures precise control over which component is activated.

For general actions that any capable app can perform, implicit intents are ideal. Instead of targeting a specific component, you define an action, and the Android system resolves it by presenting a list of apps that can handle the request. Here are two examples:

- Capturing media: To capture an image or video, raise an implicit intent with ACTION_IMAGE_CAPTURE or ACTION_VIDEO_CAPTURE. The system displays a list of camera apps able to fulfill this request.

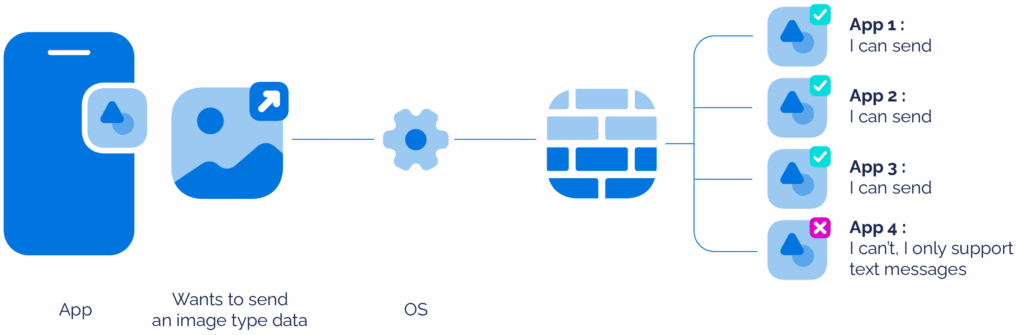

- Sending image data: To share an image, create an intent with ACTION_SEND and specify the image data. The operating system then shows a list of apps (e.g., messaging or email apps) capable of handling image sharing.

An intent consists of several key parameters that define its purpose and behavior:

- Action: Indicates the operation to perform, such as ACTION_VIEW (to display data), ACTION_SEND (to share data), or ACTION_EDIT (to modify data).

- Data: A URI specifying the data tied to the action, such as a web URL for ACTION_VIEW or a contact URI for ACTION_EDIT.

- Category: An optional field providing extra context about the component that should handle the intent. For example:

- CATEGORY_BROWSABLE signals that the target activity can be safely launched from a web browser.

- Categories like CATEGORY_APP_EMAIL or CATEGORY_APP_MUSIC help the Android system and app launchers categorize apps by their primary function.

- Extras: Key-value pairs carrying additional information to the target component, such as specific settings or data payloads.

- Component name: Specifies the exact component (e.g., an activity’s class name) to launch. Required for explicit intents.

- Flags: Control how the component is launched. For instance, FLAG_ACTIVITY_NO_HISTORY ensures the new activity isn’t retained in the history stack, meaning it’s removed from the back stack once the user navigates away.

More details about all the actions, flags, and categories are available here.

Consider the earlier example of sending an image: If only four out of five messaging apps appear in the app selection pop-up, it’s likely because one app cannot handle image data and supports only text messages. This is where intent filters come in, which apps use to declare the types of intents they can process. Intent filters ensure that only compatible apps are presented to the user, enhancing efficiency and user experience.

Intent filters

Intent filters act like a net, catching specific intents sent across the Android system and directing them to the right app components (e.g., activities). They filter intents based on three key attributes: action, data, and category. By defining these in an app’s manifest, you control which components respond to which intents, enabling seamless communication within and between apps.

Let’s explore this with practical examples of how Branch redirects users to the app.

Deep links: Opening web URLs in your app

To enable deep linking — where your app opens specific web URLs — you define intent filters with HTTP/HTTPS schemes. For example:

<intent-filter android:autoVerify="true">

<action android:name="android.intent.action.VIEW" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.BROWSABLE" />

<data android:scheme="https" android:host="example.app.link" />

</intent-filter>

This setup allows your app to handle links like https://example.app.link. When a user clicks such a link, Android checks all apps capable of opening it — including browsers, which can handle any HTTP/HTTPS URL. This often results in a chooser dialog showing your app and browser options.

Improving user experience with link verification

Showing a chooser dialog every time isn’t ideal. Android’s link verification feature solves this. By hosting a Digital Asset Links (DAL) JSON file at https://example.app.link/.well-known/assetlinks.json and adding android:autoVerify=”true” to the intent filter, the OS verifies your app’s ownership of the domain during installation. If verified, clicking the link opens your app directly, skipping the chooser.

Here’s how it works:

- You host the DAL file on your domain. Branch does it automatically on the configured domain, either Branch’s own app.link subdomain or any custom domain/subdomain.

- The OS checks it when your app is installed.

- Verified links are marked, ensuring a seamless experience.

Other intent filter examples

Filtering by data type: Handling images

Intent filters can specify the type of data a component can handle, such as images. Here’s an example where the ImageEditorActivity catches intents for sending any image type:

<activity android:name=".ImageEditorActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.SEND" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

<data android:mimeType="image/*" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

The image/* MIME type means this activity can handle any image format (e.g., PNG, JPEG). Now, for a more specific case, the JpegImageViewerActivity only accepts JPEG images:

<activity android:name=".JpegImageViewerActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.SEND" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

<data android:mimeType="image/jpeg" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

To trigger these, you’d create an intent like this:

Intent shareIntent = new Intent(Intent.ACTION_SEND);

shareIntent.setType("image/*");

shareIntent.putExtra(Intent.EXTRA_STREAM, imageUri);

This intent signals the system to share an image (via imageUri). Both activities could respond since the intent’s MIME type is image/*, but if the image is a JPEG, the system may prioritize the more specific JpegImageViewerActivity.

Custom URI schemes: Opening locations in Google Maps

Intent filters also handle custom URI schemes, allowing apps like Google Maps to respond to specific requests. For example, to open a location:

Uri gmmIntentUri = Uri.parse("geo:37.7749,-122.4194");

Intent mapIntent = new Intent(Intent.ACTION_VIEW, gmmIntentUri);

Google Maps catches this intent because its MapViewerActivity has an intent filter like this:

<activity android:name=".MapViewerActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.VIEW" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.BROWSABLE" />

<data android:scheme="geo" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

The geo scheme ensures this intent opens in Google Maps, showing the specified coordinates. For navigation, Google Maps uses another scheme:

Uri gmmIntentUri = Uri.parse("google.navigation:q=Taronga+Zoo,+Sydney+Australia");

Intent mapIntent = new Intent(Intent.ACTION_VIEW, gmmIntentUri);

The corresponding intent filter is:

<activity android:name=".NavigationActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.VIEW" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.BROWSABLE" />

<data android:scheme="google.navigation" />

<data android:host="*" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

Here, google.navigation directs the intent to start navigation to the Taronga Zoo in Sydney.

Why intent filters matter

Intent filters are the backbone of Android’s intent system, enabling apps to declare what they can do — whether it’s handling images, opening custom URIs, or responding to web links. They facilitate communication between app components and across apps, making the ecosystem modular and user friendly.

By carefully crafting intent filters, you ensure the right component catches the right intent, enhancing both functionality and user experience.